Barbara W. Trautner, Nicolas W. Cortes-Penfield, Kalpana Gupta, Elizabeth B. Hirsch, Molly Horstman, Gregory J. Moran, Richard Colgan, John C. O’Horo, Muhammed S. Ashraf, Shannon Connolly, Dimitri M. Drekonja, Larissa Grigoryan, Angela Huttner, Gweneth Lazenby, Lindsay Nicolle, Anthony Schaeffer, Sigal Yawetz, Valéry Lavergne

July 17, 2025

IDSA has released the first IDSA guidelines on management and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections (cUTIs). These guidelines provide practical advice for clinicians who manage patients with cUTIs in inpatient and outpatient settings. These guidelines expand the scope of prior UTI guidelines to address complicated UTI, provide a clinically-relevant classification of uncomplicated and complicated UTI, guide the empiric choice of antibiotics for complicated UTI through a step-wise process, offer a recommendation for the timing of IV to oral switch, and address duration of therapy. The panel’s recommendations are based upon evidence derived from systematic literature reviews and adhere to a standardized methodology for rating the certainty of evidence and strength of recommendation according to the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach.

Introduction

The prior version of the IDSA UTI guidelines focused on uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women, omitting complicated UTI (cUTI) and UTI in men.7 Since the publication of those guidelines, many randomized, controlled trials assessing new antimicrobials for cUTI in both women and men have been published. Women have a lifetime risk of 53% of experiencing UTI. While UTI is uncommon in men prior to age 50, their lifetime risk is a nontrivial 14%.8 Risk of experiencing a UTI increases with age in both sexes.9 Given the aging US population, UTI in men is a salient issue, as is UTI in women. Fortunately, a reasonable evidence base now exists to support guidelines for treatment of cUTI in men and women.

Gram-negative urinary organisms collected from outpatients across all regions of the United States now have antimicrobial resistance rates above the thresholds recommended for using antibiotics as empiric treatment of UTI in the 2010 guidelines.7 In the face of these concerningly high rates of resistance, the evidence needed to guide empiric choice of antibiotics for treating UTIs needs to be reevaluated.

Classifications

These classifications are endorsed by AMMI-CA, ASM, AUA, ESCMID, SAEM, SHM, and SIDP

Section last reviewed on 05/12/2025

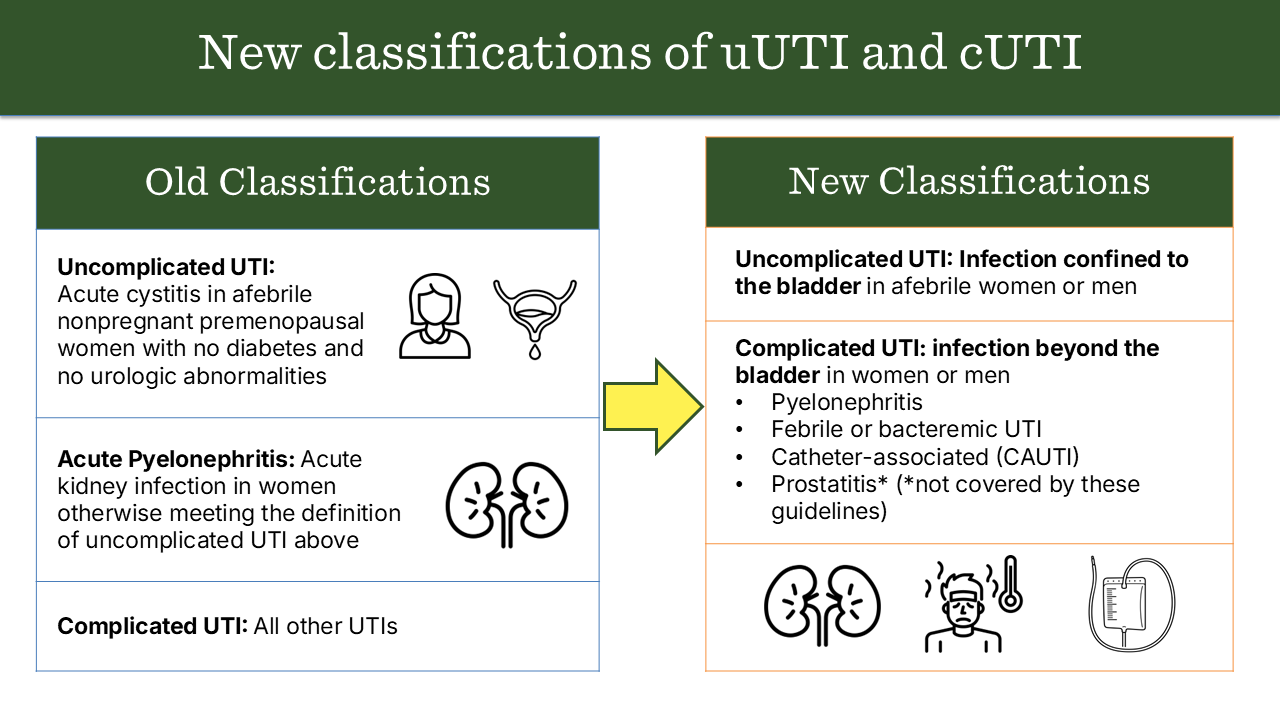

We perceived a need to update the classifications of uncomplicated and complicated UTI to better align with clinical practice, become more congruent with the available data on male UTI, and better guide management decisions. We therefore focused our revised classifications of uncomplicated and complicated UTI on the presence or absence of localized or systemic symptoms, particularly fever, that would suggest the infection had progressed beyond the bladder. We also focused the revised classifications on factors that would be readily apparent to the treating clinician at the point of care (e.g., vital signs and catheterization) rather than factors that might not be apparent without a urologic evaluation (e.g., anatomic abnormalities or urinary retention). Please refer to the full manuscript for nuances of the classifications.

Figure 1.0: Comparing prior and updated classifications of uncomplicated and complicated UTI

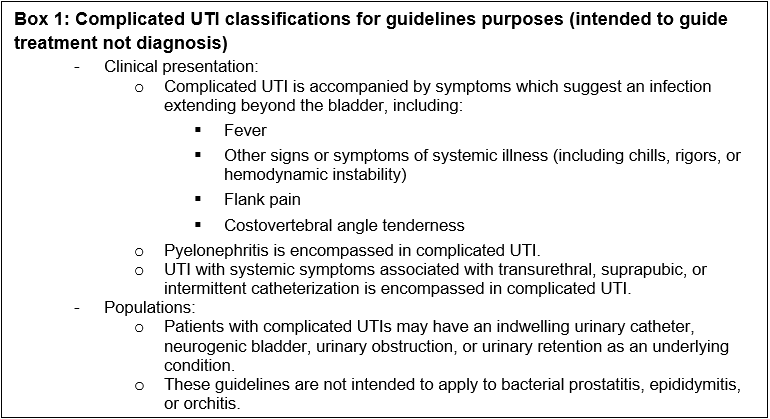

Box 1: Complicated UTI classifications for guidelines purposes (intended to guide treatment not diagnosis)

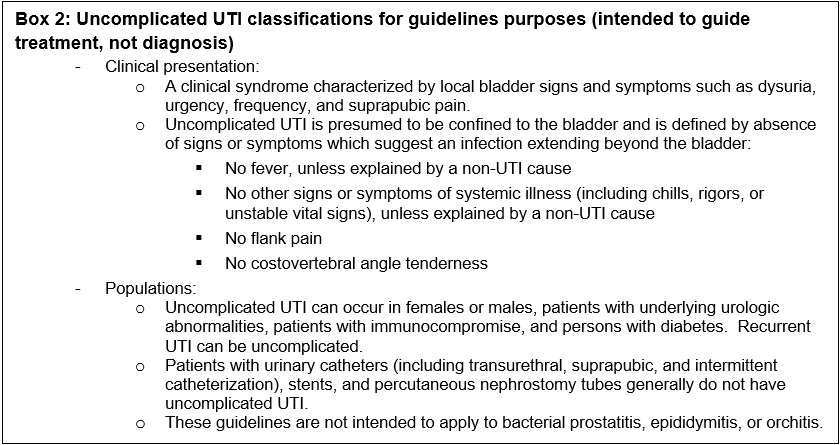

Box 2: Uncomplicated UTI classifications for guidelines purposes (intended to guide treatment, not diagnosis)

Methods

The panel included physicians and pharmacist with expertise in infectious diseases, medical microbiology, hospital medicine, primary care, emergency medicine, gynecology-obstetrics, urology, and pharmacology. The following organizations reviewed and provided feedback on the associated manuscripts: SIDP (Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists), AAFP (American Academy of Family Physicians), SHM (Society of Hospital Medicine), AUA (American Urological Association), ASM (American Society of Microbiology), SAEM (Society for Academic Emergency Medicine), AMMI-CA (Association of Medical Microbiology and the Infectious Disease Canada), European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID).

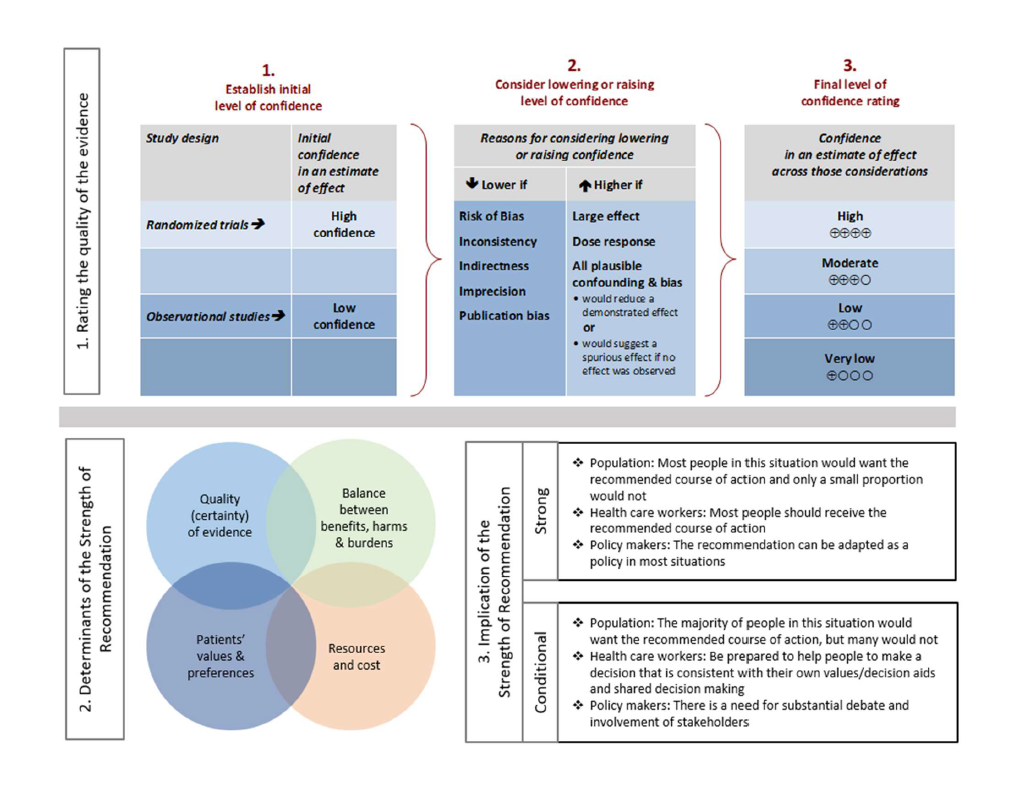

For each question, a systematic review was performed to identify relevant studies, and the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach was followed for assessing the certainty of evidence and strength of recommendation (Figure 2.0).

Details of the systematic review and guideline development processes are available in the supplemental materials for each included manuscript.

Figure 2.0. Approach and implications to rating the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations using GRADE methodology (unrestricted use of figure granted by the U.S. GRADE Network)

Recommendations on the Selection of Antibiotic Therapy for Complicated UTI

These recommendations are endorsed by AMMI-CA, ASM, AUA, ESCMID, SAEM, SHM, and SIDP

Section last reviewed on 05/12/2025

Last literature search conducted September 2024

[View supplemental material here]

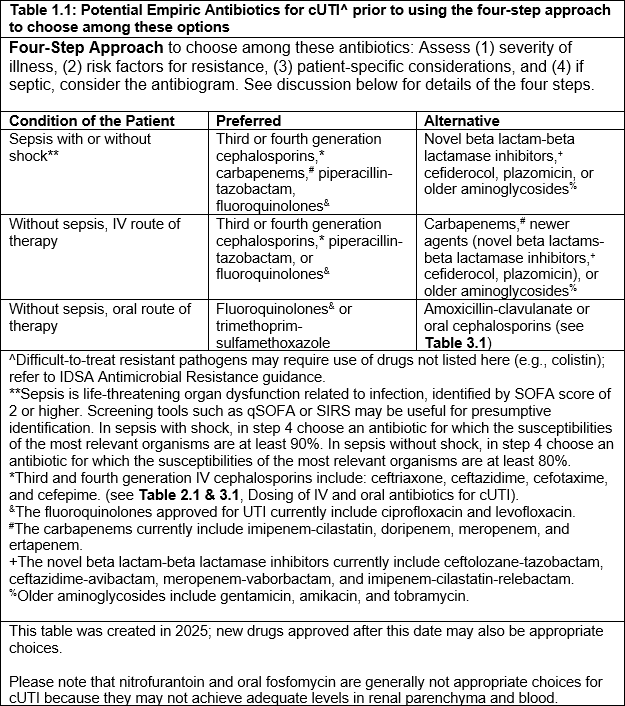

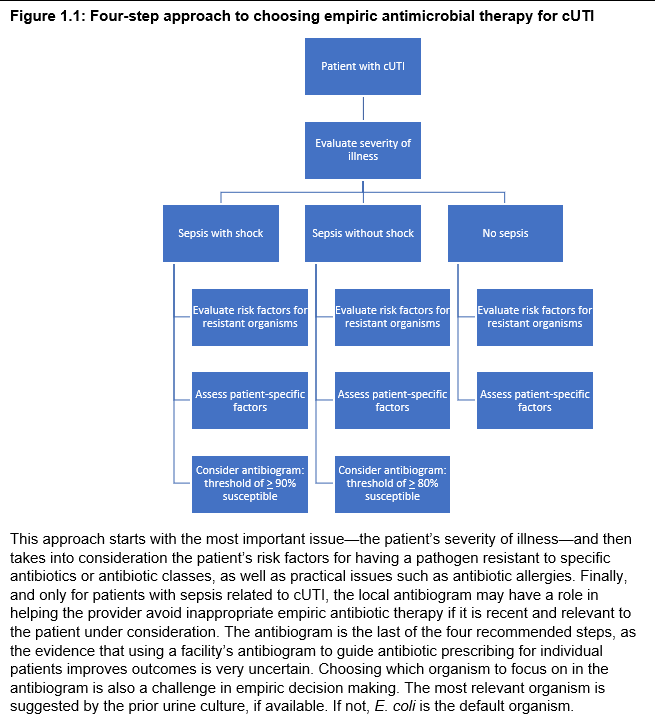

The scope of this clinical question is the empiric choice of antibiotics in suspected cUTI. The guidelines categorize empiric antibiotic choices as preferred versus alternative, stratified for severity of illness. However, when choosing among these antibiotics for a specific patient, a four-step process should be followed to account for changing resistance patterns and individualized patient needs. The guidelines below first discuss the evidence for specific antibiotics or classes of antibiotics that can be used as empiric therapy for cUTI. Then, the four-step approach is discussed, with explanations of the evidence on the potential impact of inappropriate initial antibiotic therapy, the predictive value of specific risk factors for having a resistant uropathogen (including prior urine cultures and prior antibiotic exposure), and modeling approaches for establishing what threshold to use on the antibiogram when choosing empiric antibiotics for a cUTI patient with sepsis. Specifically, the four-step approach is to assess: (1) severity of illness, (2) risk factors for resistance, (3) patient-specific considerations, and (4) if septic, consider the antibiogram. See discussion below for details of the four steps. Finally, the guidelines address choice of definitive therapy when culture results are available.

A. Initial Selection Among Empiric Antibiotic Options for Complicated UTI

In patients with cUTI, which classes of empiric antibiotic therapy should initially be prioritized?

Recommendations

a) For patients with sepsis due to complicated UTI, we suggest initially selecting among the following antibiotics, using the four-step assessment (Figure 1.1): third- or fourth-generation cephalosporins, carbapenems, piperacillin-tazobactam, or fluoroquinolones, rather than newer agents (novel beta lactam-beta lactamase inhibitors, cefiderocol, plazomicin) or older aminoglycosides (conditional recommendation, very low to moderate certainty of evidence).

Remarks

-

- See Table 1.1 for a more complete list of empiric antibiotic therapy options.

- Please refer to the four-step approach in Figure 1.1 to choose among these antibiotics for the specific patient (i.e., severity of illness, risk factors for having resistant uropathogen, patient-specific considerations, and antibiogram).

- Agents with broader spectrum of activity against organisms other than Enterobacterales (e.g. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, enterococci, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) may be considered for patients with sepsis in whom the diagnosis of cUTI is not clear or who are suspected to have cUTI due to these pathogens.

Comments

-

- This recommendation places a higher value on providing early, appropriate empiric antibiotic therapy to prevent mortality while deferring stewardship considerations to definitive therapy.

- The certainty of evidence was moderate for all classes of antibiotics, except for third and fourth generation cephalosporins, and older aminoglycosides, for which the certainty of evidence was very low.

b) For patients with suspected complicated UTI without sepsis, we suggest initially selecting among the following antibiotics, using the four-step assessment (Figure 1.1): third- or fourth-generation cephalosporins, piperacillin-tazobactam, or fluoroquinolones, rather than carbapenems and newer agents (novel beta lactam-beta lactamase inhibitors, cefiderocol, plazomicin) or older aminoglycosides (conditional recommendation, very low to moderate certainty of evidence).

Remarks

-

- See Table 1.1 for a more complete list of empiric antibiotic therapy options.

- Please refer to the four-step approach in Figure 1.1 to choose among these antibiotics for the specific patient (i.e., severity of illness, risk factors for having resistant uropathogen, and patient-specific considerations).

- Other agents (e.g., trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin-clavulanate, first or second-generation cephalosporins) are less well studied but may be appropriate in select settings or situations for empiric oral treatment of cUTI.

Comments

-

- This recommendation places a higher value on antibiotic stewardship considerations in patients with cUTI who are not septic and in whom the risk of infection-related mortality is low while also considering costs, resources, and practical aspects of antibiotic administration

- The certainty of evidence was moderate for all classes of antibiotics, except for third and fourth generation cephalosporins and older aminoglycosides, for which the certainty of evidence was very low.

Table 1.1: Potential Empiric Antibiotics for CUTI prior to using the four-step approach to choose among these options

B. Process to Guide Empiric Antibiotic Choice for Complicated UTI

To optimize the selection of empiric antibiotic therapy for patients with suspected complicated UTI, we propose the following four-step approach: 1) assess the severity of illness (for initial prioritization of empiric antibiotic therapy), 2) consider patient-specific risk factors for resistant uropathogens (for optimization of coverage), 3) evaluate other patient-specific considerations (to reduce the risk of adverse events), and 4) for patients with sepsis, consult a relevant local antibiogram if available (to further improve the likelihood of giving appropriate empiric therapy in septic patients).

Figure 1.1: Four-step approach to choosing empiric antimicrobial therapy for cUTI

STEP 1: SEVERITY OF ILLNESS (initial prioritization of empriric antibiotic therapy)

In patients with suspected cUTI (including pyelonephritis), should selection of empiric antibiotic therapy be guided by severity of illness?

Recommendation

I. For patients with suspected complicated UTI (including pyelonephritis), we suggest that the selection of empiric antibiotic therapy be initially guided by the severity of illness, specifically by whether the patient is in sepsis or not (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

Remarks

-

- Sepsis is defined per the Sepsis-3 Task Force as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. These patients can be identified by SOFA score increase of 2 points or more, reflecting an in-hospital mortality greater than 10%, or presumptively identified with screening tools such as qSOFA or SIRS.20,21

STEP 2: PATIENT-SPECIFIC RISK FACTORS FOR RESISTANT UROPATHOGENS (optimization of coverage)

In patients with cUTI (including pyelonephritis), should selection of empiric antibiotic therapy be guided by patient-specific prior urine culture results and patient-specific risk factors for resistant uropathogens to optimize selection)?

Recommendations

I. In patients with complicated UTI (including acute pyelonephritis), we suggest avoiding antibiotics to which the patient has had a resistant pathogen isolated from the urine previously (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence)

Remarks

-

- More recent urine cultures may be a better guide than more distant urine cultures.

- The time frame for paired cultures (urine samples collected from the same patient at different occasions) varied, but the median was 3-6 months.

II. In patients with complicated UTI (including acute pyelonephritis), we suggest avoiding fluoroquinolones if the patient has been exposed to that class of antibiotic in the past 12 months (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

Remark

-

- More recent antibiotic exposure may be a better guide than more distant antibiotic exposure.

STEP 3: OTHER PATIENT-SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS (prevention of possible undesirable events)

In patients with cUTI (including pyelonephritis), should selection of empiric antibiotic therapy be further guided by patient-specific considerations?

Recommendation

I. In patients suspected of cUTI, empiric antibiotic therapy selection should account for patient-specific considerations (e.g. risk of allergic reaction, contraindications, or drug-drug interactions) to avoid preventable adverse events (good practice statement).

STEP 4: ANTIBIOGRAM (tailoring empiric antibiotic therapy in septic patients)

In patients with cUTI (including pyelonephritis), should selection of empiric antibiotic therapy be further tailored by consulting an antibiogram?

Recommendations

I. In patients with sepsis assumed to be caused by complicated UTI (including acute pyelonephritis), we suggest using an antibiogram to further tailor empiric antibiotic choice only if the antibiogram is local, recent, and relevant to the patient (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

Remarks

-

- An antibiogram is considered local if derived from the same healthcare facility, recent if based on data from the prior 12 months and relevant to the patient if based on organisms from a similar patient population.

- If an antibiogram is being used to further tailor empirical antibiotic choice, consider selecting an antibiotic for which 90% or more of the most relevant organism(s) are susceptible in patients in septic shock, or for which 80% or more of the most relevant organism(s) are susceptible in patients with sepsis without shock. These cutoffs are based on modeling of increased mortality risk associated with inappropriate empiric antibiotics in sepsis and septic shock.

- Septic shock is defined by the Sepsis-3 Task Force as a subset of sepsis in which despite volume resuscitation, vasopressors are required to maintain blood pressure and serum lactate level is greater than 2 mmol/L, reflecting an in-hospital mortality greater than 40%.20,21

II. For patients with suspected complicated UTI without sepsis (including acute pyelonephritis), we make no specific recommendation about using an antibiogram to further tailor empiric antibiotic choice (no recommendation, knowledge gap).

Remarks

-

- Patients who are not septic have a lower risk of mortality from cUTI (less than or equal to 5%) and initial inappropriate empiric antibiotic choice has little impact on mortality. Routine use of broader-spectrum agents in suspected complicated UTI without sepsis may drive antimicrobial resistance without substantial patient benefit.

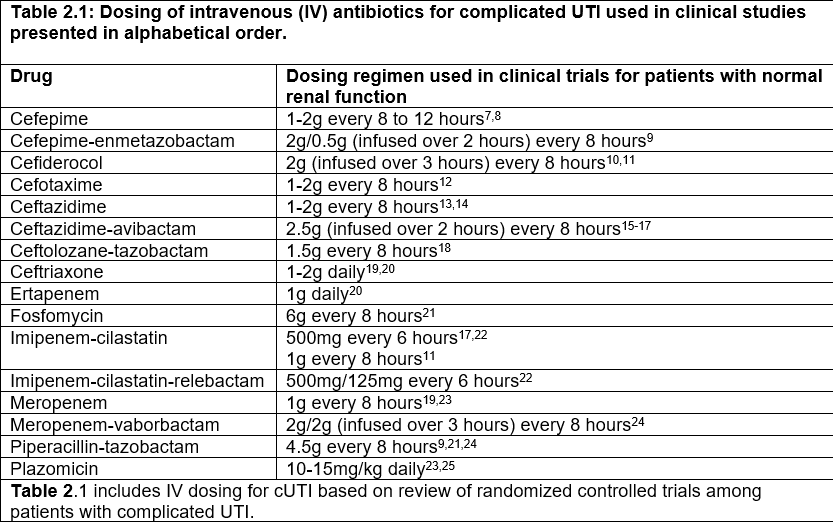

Table 2.1: Dosing of intravenous (IV) antibiotics for complicated UTI used in clinical studies presented in alphabetical order

C. Selection of Definitive Antibiotic Therapy for Complicated UTI

In patients with microbiologically confirmed cUTI, should definitive effective antibiotic therapy be targeted based on the results of urine culture rather than continuing empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics?

Recommendation

I. In patients with confirmed complicated UTI, we suggest selecting a definitive effective antibiotic with a targeted spectrum based on the results of urine culture (identification and susceptibility) as soon as these are available, rather than continuing empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics for the complete duration of treatment (conditional recommendation, low certainty of the evidence).

Comment

-

- This recommendation places a high value on de-escalating antibiotic therapy based on culture results (stewardship considerations) while optimizing the effectiveness of therapy (improving clinical cure and reducing recurrence of infection). De-escalation may be less practical in cases of cUTI managed in the outpatient setting.

References

[View full reference list here]

Recommendations on the Timing of Intravenous to Oral Antibiotics Transition for Complicated UTI

These recommendations are endorsed by AMMI-CA, ASM, AUA, ESCMID, SAEM, SHM, and SIDP

Section last reviewed on 05/12/2025

Last literature search conducted September 2024

[View supplemental material here]

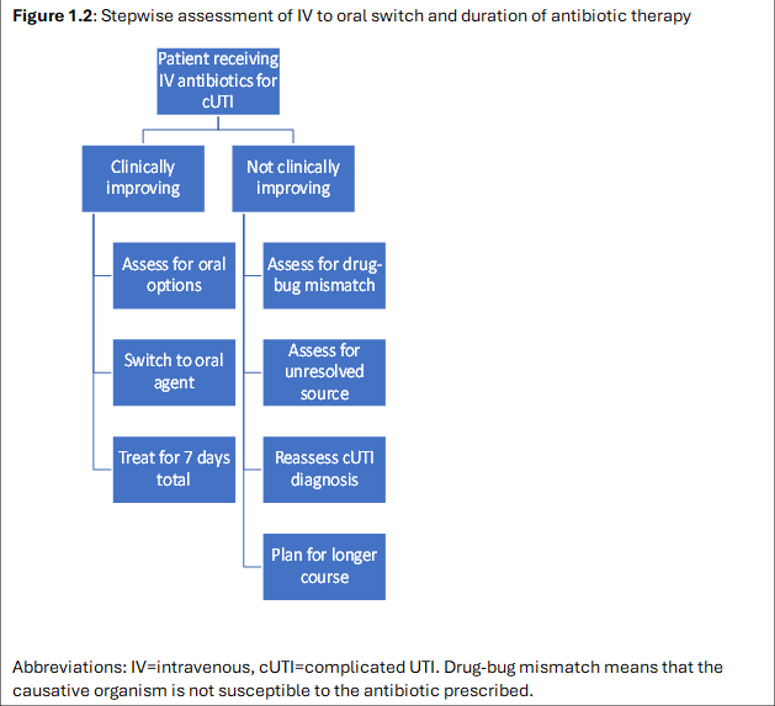

An increasing number of clinical trials support early IV treatment with transition to oral therapy for infectious syndromes.1,2 From a pharmacological point of view, antibiotic efficacy depends on the levels of the antibiotic obtained in serum and tissue, not the route of administration.2 In practice, providers often switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics during the course of therapy for complicated UTI, once a patient is improving. We sought evidence about whether such transition impacts clinical outcomes of cUTI treatment versus continuing intravenous therapy. We also looked for information from clinical trials to guide the timing of this switch and appropriate circumstances for switching to the oral route.

From a practical perspective, an IV to oral switch, if equivalent in terms of outcomes, would be desirable because switching can reduce the need for intravenous access, complications from intravenous devices, nursing time and effort to administer the medication, volume of fluid and sodium given to the patient, duration of hospitalization, healthcare costs, and inconvenience to the patient.

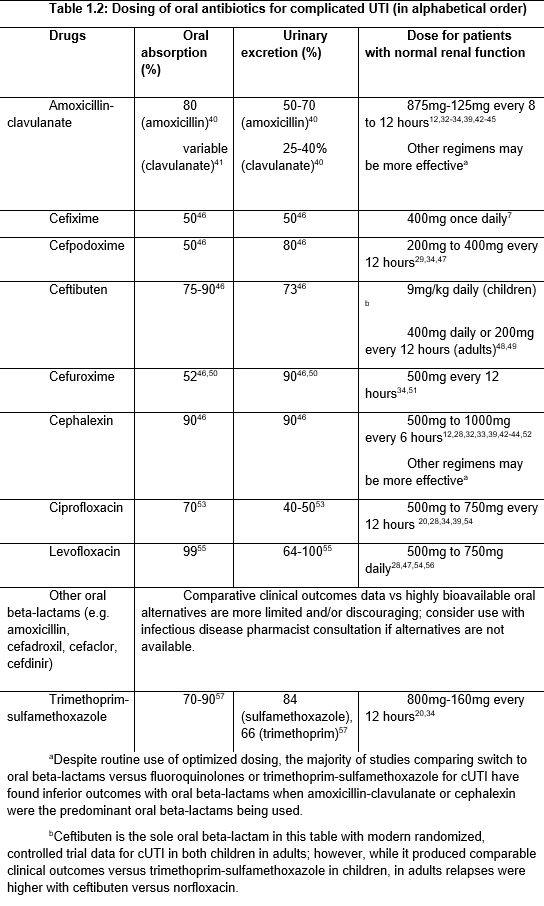

Some patients with cUTI can be managed entirely with oral antibiotics in the outpatient setting. Please see a discussion of this topic in Clinical Question 1, under the section on “Oral antibiotics for cUTI.” Also see Table 1.2 below, Dosing of oral antibiotics for complicated UTI.

In patients who are being treated parenterally for cUTI, are clinically improving, can take an oral medication and for whom an oral option is available, should parenteral therapy be transitioned to oral rather than continued for the complete duration of therapy?

Recommendations

I. In patients with complicated UTI (including acute pyelonephritis) treated initially with parenteral therapy who are clinically improving, able to take oral medication, and for whom an effective oral option is available, we suggest transitioning to oral antibiotics rather than continuing parenteral therapy for the remaining treatment duration (conditional recommendation, low certainty of the evidence)

Comments

-

- This recommendation places a high value on reducing avoidable intravenous catheter-related adverse events, costs, and resources, as well as taking into account practical aspects of antibiotic administration.

- The trials supporting this recommendation mostly excluded patients with indwelling urinary catheters, sepsis or septic shock, immunocompromised states, severe renal insufficiency, and functional or structural abnormalities of the urinary tract. Some patients in these subpopulations may need an individualized plan of therapy.

- An effective antimicrobial agent means that the antibiotic achieves therapeutic levels in the urine and relevant tissue and is active against the causative pathogen.

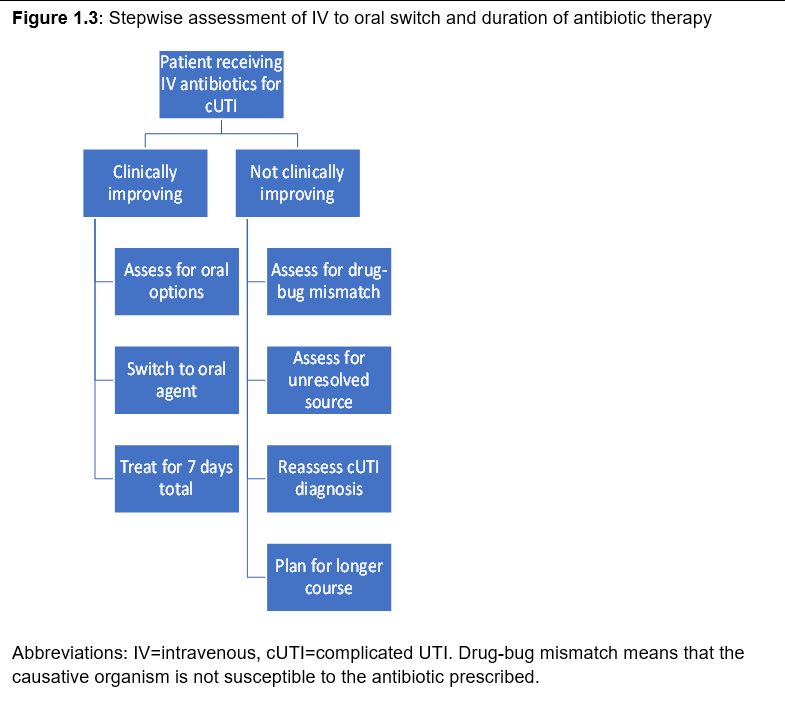

- Refer to Figure 1.2 for a stepwise assessment of the intravenous to oral switch and the duration of antibiotic therapy.

II. In patients presenting with complicated UTI (including acute pyelonephritis) and associated Gram-negative bacteremia treated initially with parenteral therapy who are clinically improving, able to take oral medication, and for whom an effective oral option is available, we suggest transitioning to oral antibiotics rather than continuing parenteral therapy for the remaining treatment duration (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of the evidence).

Comments

-

- The trials supporting this recommendation mostly included patients who were afebrile, hemodynamically stable, and had achieved source control (relief of any urinary obstruction) before transitioning to oral antibiotics.

- An effective antimicrobial agent for bacteremic patients means that the antibiotic achieves therapeutic levels in the bloodstream, urine, and relevant tissue and is active against the causative pathogen.

- Refer to Figure 1.2 for a stepwise assessment of the intravenous to oral switch and the duration of antibiotic therapy.

Figure 1.2: Stepwise assessment of IV to oral switch and duration of antibiotic therapy

Table 1.2: Dosing of oral antibiotics for complicated UTI (in alphabetical order)

References

[View full reference list here]

Recommendations on the Duration of Antibiotics for Complicated UTI

This recommendation is endorsed by AMMI-CA, ASM, AUA, ESCMID, SAEM, SHM, and SIDP

Section last reviewed on 03/12/2025

Last literature search conducted September 2024

[View supplemental material here]

The duration of therapy is important for antibiotic stewardship and has relevance to patients’ wellbeing. Although it is unclear whether shortening an antibiotic course from 14 to 7 days has a meaningful impact on the individual’s microbiome,1 broader societal concern to reduce overall antibiotic use remains a priority.2 Many studies show that infections are often treated for longer than guidelines recommend, and evidence demonstrates that each additional day of antibiotics increases the risk of patient harm, particularly in terms of adverse effects, and can negatively impact patient well-being.3-5 These risks to individuals are further compounded by the public health concern of increased selection for and transmission of multidrug resistant organisms. Both IDSA guidelines on establishing antibiotic stewardship programs6 and the CDC Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs7 recommend implementing strategies to reduce antibiotic therapy to the shortest effective duration.

In patients presenting with complicated UTI (cUTI) with a clinical response to therapy, should total duration of antibiotics be prolonged to >7 days rather than shorter (<=7 days)?

Recommendations

I. In patients presenting with complicated UTI (including acute pyelonephritis) and who are improving clinically on effective therapy, we suggest treating with a shorter course of antimicrobials, using either 5-7 days of a fluoroquinolone (conditional recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence) or 7 days of a non-fluoroquinolone antibiotic (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence), rather than a longer course (10-14 days).

Definitions

-

- An effective antimicrobial agent achieves therapeutic levels in the urine and relevant tissue and is active against the causative pathogen.

- The duration of therapy is counted from the first day of effective antibiotic therapy.

Comments

-

- Most studies supporting this recommendation excluded patients with indwelling urinary catheters, severe sepsis, immunocompromising conditions, abscesses in the urinary tract, chronic kidney disease, bacterial prostatitis, complete urinary obstruction, or undergoing urologic surgical procedures. Some patients in these subpopulations may be at higher risk for complications or treatment failure and may need an individualized duration of therapy.

- Men with febrile UTI in whom acute bacterial prostatitis is suspected may benefit from a longer treatment duration (i.e., 10-14 days), although evidence to guide the optimal duration in this subgroup is lacking.

- This recommendation is driven by evidence from trials that primarily studied fluoroquinolones during a time when fluroquinolone resistance was less common. Evidence for short courses of oral beta lactams in cUTI is more limited, and higher doses may be required for efficacy.

- Consider evaluation for an ongoing nidus of infection requiring source control in patients who do not have prompt clinical improvement.

- This recommendation places a high value on antibiotic stewardship considerations as well as reducing the burden of antimicrobial administration from a healthcare perspective and reducing the burden of taking antibiotics from a patient perspective.

- Refer to Figure 1.3 for a stepwise assessment of the intravenous to oral switch and the duration of antibiotic therapy.

II. In patients presenting with complicated UTI with associated Gram-negative bacteremia and who are improving clinically on effective therapy, we suggest treating with a shorter course (7 days) of antimicrobial therapy rather than a longer course (14 days) (conditional recommendation, low certainty in the evidence).

Definitions

-

- An effective antimicrobial agent for bacteremic patients means that the antibiotic achieves therapeutic levels in the bloodstream, urine, and relevant tissue and is active against the causative pathogen.

- The duration of therapy is counted from the first day of effective antibiotic therapy.

Comments

-

- Men with febrile, bacteremic UTI in whom acute bacterial prostatitis is suspected may benefit from a longer treatment duration (i.e., 10-14 days), although evidence to guide the optimal duration in this subgroup is lacking.

- Consider evaluation for an ongoing nidus of infection requiring source control in patients who do not have prompt clinical improvement.

- This recommendation places a high value on antibiotic stewardship considerations as well as reducing the burden of antimicrobial administration from a healthcare perspective and reducing the burden of taking antibiotics from a patient perspective.

- Refer to Figure 1.3 for a stepwise assessment of the intravenous to oral switch and the duration of antibiotic therapy.

Figure 1.3: Stepwise assessment of IV to oral switch and duration of antibiotic therapy

References

[View full reference list here]

Patient Perspectives

The evidence base for our guidelines is drawn from the general population of patients with cUTI who are healthy enough to enter a clinical trial. In this population, treatment is expected to relieve the symptoms of the acute infection and prevent recurrence. However, a subset of the cUTI population suffers from chronic urinary symptoms. Recommendations about diagnosis or treatment of chronic UTI are outside of the scope of our cUTI guidelines. However, the guidelines panelists acknowledge that patients who suffer from acute, recurrent, or chronic UTI symptoms should be heard. Several large patient advocacy groups support people who suffer from recurrent UTI or the inadequately defined entity of chronic UTI. We invited three representatives from these groups to participate in our patient advisory group. For details of their perspectives, lived experiences, and suggested research topics, please review the full manuscript.

Notes

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the important contributions of our four patient representatives (Carolyn Turner, Lisa Tecklenburg, Valerie Price, Laura Helgeson) and the two librarians (Elizabeth Kiscaden and Mary Beth McAteer). We also appreciate the efforts of our three external reviewers (Thomas Mac Hooton, Emily Spivak, and Bryan Alexander) and reviews by the Standards and Practice Guidelines Subcommittee. In addition, we would like to acknowledge IDSA staff Senam Attipoe, Genet Demisashi, and Jon Heald for their continual support and guidance developing the guidelines.

Conflicts of Interest

Possible conflicts of interest. Evaluation of relationships as potential conflicts of interest is determined by a review process. The assessment of disclosed relationships for possible COIs is based on the relative weight of the financial relationship (i.e., monetary amount) and the relevance of the relationship (i.e., the degree to which an association might reasonably be interpreted by an independent observer as related to the topic or recommendation of consideration).

The following panelists have reported relationships with indicated companies since 2019, when the guideline work began. B.T. served as an advisor for Genentech, GSK, Phiogen Pharma, and Paratek Pharmaceuticals; received research funding from Genentech and Zambon Pharmaceuticals; received grant funding from the MacDonald Research Foundation, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, VA HSR&D, CDC, NIH, Mike Hogg Foundation, Neilsen Foundation, and VA RR&D; engaged in activity with Infectious Diseases Board Review Course, Warren Alpert School of Brown University Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine PriMed, and UpToDate; owns intellectual property for Phiogen Pharma; and owned stocks in Abbott Laboratories, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Abbvie, and Pfizer (all divested when B.T. learned of the individual stock ownership). N.C.P. received funding from Duke University. K.G. served as a consultant for Iterum Therapeutics, Tetraphase Pharmaceutical, Paratek Pharmaceutical, First Light Diagnostics, Ocean Spray Inc, Shionogi Inc, Nabriva Therapeutics, Utility Therapeutics, Qiagen Diagnostics, Rebiotix, Spero Therapeutics; serves as a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, PhenUtest (Innotive), CarbX and PRIME Education; receives renumeration from Up to Date, Inc. Pri-Med and PRIME Education; owned equities in Pfizer Pharmaceutical (past), and Fidelity Managed Investment Account; received research grant funding from VA Health Services Research & Development, VA Cooperative Studies Program, NIAID, and NIH. E.H. receives funding from Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; receives honoraria from SIDP; served as an advisor for Nabriva Pharmaceuticals, Merck, GlaxoSmithKlin, Paratek Pharmaceuticals and MeMed; received funding from Merck; engages in activity with SIDP and CLSI. M.H. received research grants from AHA, VA QUERI, Veterans Affairs Health Systems Research, National Institute on Aging, Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine, and Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; receives funding from Veterans Affairs Health Systems Research. G.M. served as an advisor for Light AI and Qiagen; received funding from Light AI, Contrafect, Nabriva, and NIH; engaged in activity with Annals of Emergency Medicine; owns stock in Light AI; receives funding from Abvacc. R.C. served as an advisor for the GlaxoSmithKlin, Biofire and Rebiotix. J.O. received funding from MITRE Corporation. M.S.A. received funding from Merck & Co. Inc and Nebraska DHHS HAI/AR Program (through CDC grants); served as a member and vice chair of PALTmed's Infection Advisory Committee (IAC) and chair of PALTmed’s IAC UTI workgroup; served as a member of ASCP’s AS and Infection Control committee; served as vice president and president for Nebraska Infection Control Network; served as a member of SHEA’s education committee and Learning CE committee; and served as member of IDSA antimicrobial resistance committee; serves as board member and immediate past president for Nebraska Infection Control Network; serves as chair of PALTmed's infection prevention and control committee (previously infection advisory committee) and member of PALTmed's state advocacy committee (previously state based policy and advocacy subcommittee) and clinical practice steering committee; serves as a member of CSTE HAI/AR subcommittee; is member of the SHEA Long-Term Care Special Interest Group, was a member of the COVID-19 State Collaboration Task Force of PALTmed; worked on development of infection control guidance for nursing homes with SHEA and is working on development of infection control guidance for LTACHs and antibiotic initiation guidance for nursing homes with SHEA and also on nursing home infection control educational module development for front-line staff with SHEA; and accepted invitation to serve on HICPAC but onboarding was not completed. D.D. received funding from VA CSP, VA Merit Review, VA Cooperative Studies Program, CDC Tuberculosis Trials Consortium, and honoraria from UpToDate. L.G. received funding from Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group, NIH, Zambon Pharmaceuticals, VA Health Services Research & Development, Rebiotix, and AHRQ; receives funding from AHRQ; Neilsen Foundation, VA Health Services Research & Development and Micheal E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Seed Grant. S.C. Received honoraria for the development of sexual and reproductive health educational materials for family physicians from the American Academy of Family Physicians and California Academy of Family Physicians and received honoraria for the development of training materials on sexual health from Quest Diagnostics. A.H. received funding from Swiss National Science Foundation, and serves as the ESCMID representative on the panel. G.L. received honoraria from UpToDate; received funding from Lupin Pharmaceutical, NeuMoDx, CDC, NACCHO, NIH, HRSA, DHHS, State Office of Victims Assistance, and IDSOG. L.N. served as an advisor for Utility, Paratek, and GSK; engaged in activity with SHEA, Government of Manitoba, and ESCMID. A.J.S. served as an advisor for Spero; received funding from NIH; and engaged in activity with UpToDate, Inc. S.Y. received funding from Gilead and Dynamed; received remuneration with Dynamed; served as an advisor for Gilead; received funding from NIH/ACTG, HRSA; received royalties from UpToDate. V.L. received funding from Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Santé (FRSQ); received funding from Centre de Recherche du Centre Intégré Universitaire de Santé et de Services Sociaux du Nord-de-l’île-de-Montréal (CIUSSS_NIM). No disclosures were reported for all other authors.

Publication Disclaimer

© IDSA <2025>. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, used for text and data mining, or used for training artificial intelligence, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing, or as expressly permitted by law, by license or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. For commercial re-use, please contact reprints@oup.com for reprints and translation rights for reprints. All other permissions can be obtained through the Oxford University Press RightsLink service via the Permissions link for this paper in Clinical Infectious Diseases. For further information please contact journals.permissions@oup.com.